Quiet Strength — The Story of Shooting Touch’s Abera Jackline

By Nicholas Kairys

March 29, 2019

On Monday, March 12, Abera Jackline showed up to Nyamirama, Rwanda to do what she loves.

Her sparkling white Adidas tennis shoes shined among the clouds of dust kicking up around the sideline. Her workout outfit was planned in advance — plush navy sweatpants with a matching dotted polo. A leopard-print headband stretched across her forehead under a recently fixed combover. A glistening red band clasped over her left wrist. In her hand she carried a smartphone slightly smaller than a tablet. She took a sip from her transparent water bottle and jogged on for a substitution. Her teammates looked at her admirably and shook her hand in delight. Jackie was a guest, not a regular, at the all-women’s scrimmage at Shooting Touch’s basketball court. The other 267 women at Nyamirama dressed vastly different. They wore vibrant traditional kitenge dresses or hand-me-down shirts and shorts. Many slid on faded sandals, or had no shoes at all. A few set flip phones aside. None brought water.

Abera Jackline “Jackie,” 33, is blessed with a prosperous lifestyle compared to other women in her district. She’s independent and lighthearted. But life for her wasn’t always that way.

Jackie lives in Kayonza, not necessarily a village, but a business hub, a logistical segway to Rwanda’s capital and one of Shooting Touch’s four mainstays. In Kayonza, there is no women’s basketball program, unlike in the other three pastoral Shooting Touch communities. Women in Kayonza tend to value commerce, family care and education over — what they see as frivolous — interests such as sports. At the Kayonza Youth Center, however, Jackie was the only woman in the past five years to approach coaches with a sincere interest in basketball. She was told the only way she could practice was if she jumped into the U-18 girls’ program weekly at 6:00 pm.

So, she does. Every day. A grown woman running through drills among teenage girls.

“There was no other option,” she says, laughingly.

Jackie joined Shooting Touch organically, not seeking tangible benefits. She has a stable income, volunteers for the government and provides her own health insurance. She’s in it for something else. She’s in it for love, for her daughter, for the welfare of her community, for the resurrection of her mental health.

She’s exactly the kind of resilient woman Shooting Touch needs.

Jackie has quiet strength. The kind of strength that, if meeting her in the short term, can be mistaken for bashfulness. Anyone who knows Jackie can shoot that misrepresentation down. When she chooses to speak, you listen carefully. Her voice is gentle, but unwavering.

When she tells the story of her past, in many ways, she’s had no choice but to be strong. Jackie’s parents fled Rwanda for Uganda in 1959 as refugees of the Rwandan Revolution, a prefiguration period of violence between the Hutu and Tutsi ethnic groups. They remained in Uganda, away from their native country, for their entire lives. In 1985, Jackie was born in Uganda as a child of the continuing Rwandan border conflict. She doesn’t have many memories of her childhood in Uganda. She digs up a few flashbacks.

Jackie had an early admiration for fish. Her father would routinely take her fishing at a nearby river in the village. When they didn’t go together, he would bring home the daily catch for her to marvel at.

Jackie’s mother loved riding bicycles. She would swing Jackie up onto her lap behind the handlebars and peddle off for the market, to school, or elsewhere. Her mother started teaching her how to ride, but Jackie was so small. She tried and tried and tried, but she’d fail. The bike seat was tall.

As she spoke, the impending — very real — memories crept up and her nostalgia faded. Her father was a soldier in the Rwandan Patriotic Army (later known as the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF)) during the early period of the Rwandan genocide. In December of 1990, he was sent off for duty and never returned home — shot in the field of battle. In 1992, Jackie’s mother passed away from sickness. Like many Rwandan children born in the late 80’s and early 90’s, Jackie was an orphan. She was seven years old.

The genocide concluded in 1994 when the RPF took control of Kigali, Rwanda’s capital. With the ending of the ethnic turmoil, Jackie’s infancy in Uganda ended as well. Her extended family, in body and in spirit, could return to its true homeland. Jackie moved to Rwanda with her grandparents and two brothers. She calls her grandfather “dad.” She says he’s the largest influence on her amicable nature. He was a people person, she says. She calls him a peacemaker. The kind of person who welcomes anyone around. When she says these things, she thinks she is speaking on her “dad’s” character, but really, she’s describing herself.

Two years after Jackie’s family scrambled to piece together and settle home in Rwanda, Jackie’s grandmother passed away. Jackie was forced into a new role. “I was a girl and a wife. Two in one,” she says. She’d wake up — usually before the rising sun — and clean the house, wash clothes and prepare food for the day. Only when she was finished could she go to school. The same daily routine continued for eight years. In 2004, she dropped out of secondary school “Senior 4” at age 16, because her grandfather told her he had no money left to pay for her fees. That’s when he gave her the advice, or more appropriately the order, that changed her life.

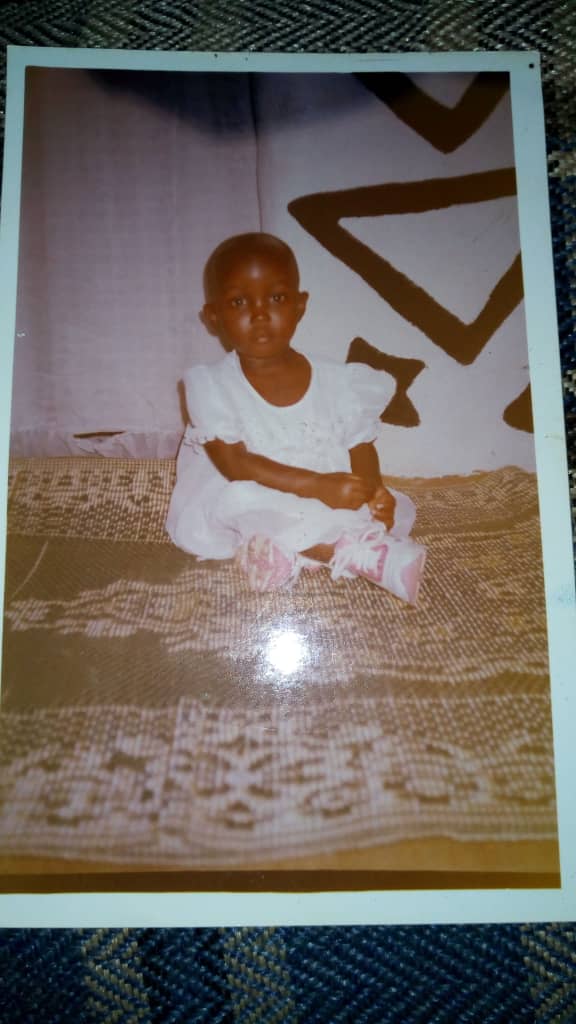

Jackie at one and a half years old

“My grandfather said to me, ‘You have to sit down and get married, there’s nothing else.’”

Jackie trusted her “dad.” She passively accepted his counsel. Soon after, a man in Jackie’s village recognized she had not been attending school. He approached her grandfather with a proposition. His offer was to help Jackie get through school, and after she finished, he’d agree to wed her. Her grandfather approved. Jackie would be off to Kigali a married woman and a student as soon as possible. A year into her marriage, at 17 years old, Jackie gave birth to her first child, a daughter named Shema and affectionately called “Queen.” Once Shema was born, Jackie recalls her new husband showing his true colors. “He became a womanizer and a drunk,” she says. “He earned his money, went to the bar, and when he came home, he had nothing. He didn’t support me or Shema.”

She couldn’t live with his antics any longer. He couldn’t continue to pay her school fees either. She ran away to her grandfather and explained her situation. He provided no answer. He didn’t have enough money to support his granddaughter and her child. Jackie had no choice but to move off on her own with her daughter. In 2006, she relocated to Nyagatare, a province of Rwanda, where she worked as a waitress. She was paid just enough to survive. She could afford the basics and only the basics — rice, soap and sugar, she says. She transferred to Kayonza, Rwanda, still working as a waitress. For two hours a day she was granted leave from work to finish secondary school and study for the national (secondary) exam. She took the exam, passed, collected her diploma, but did not receive government sponsorship.

Jackie quit waitressing and returned to Uganda in 2007 to begin university courses at a local YMCA and the pursuit of a childhood teaching degree. She had no job and no real home. After running into a family friend, Jackie found out about an aunt, her father’s sister, living in Kampala, Uganda. On meeting her for the first time, Jackie told her aunt her life story. Her aunt pitied her. She found Jackie a job working at a local supermarket. Even with the salary, Jackie still made little money. She had a child at home. She saw no route to economic prosperity, or even basic security, and so another decision was made for her.

“My aunt organized a meeting with a rich man I didn’t know,” Jackie says. “Basically, I was forced into another marriage.” Before Jackie realized what she was getting herself into, her new husband shipped her off to Kenya with him. An unfamiliar place with an unfamiliar man. She knew nothing about him. Only that he paid her aunt copious amounts of money for her hand in marriage. She didn’t understand why he — out of all people — desired her. She was told by friends and family she was attractive, yes. She was young. Thinking back, she still can’t explain the “why.” Perhaps it was because she was his first wife? He couldn’t love me, she thought, he just met me.

If he did love her, he didn’t show it.

“He would close and lock every hall of the house so I couldn’t get out. I wasn’t fine with it. When he’d come home, I’d say, ‘When you leave me, I will get out of here and not come back.’”

In more ways than one, she was trapped.

“My life — I was like a prisoner,” she says.

Through intimidation and helplessness, Jackie gave birth to a baby girl with her new husband. She had no life. Every day she nursed her newborn at home. She couldn’t go to school. She couldn’t go out. Nothing. She stayed, practically against her will.

She asked her husband one day if she could at least go back to Rwanda to see her grandfather. He reluctantly agreed and gave her money for transport. Finally, she’d be able to share her stories of marital exploitation and abuse. This could’ve been her chance out. She returned to her “dad,” the only man she loved, and maybe he loved her equally, but he couldn’t understand his daughter was drowning in peril.

“He said, ‘My daughter, just go back. Maybe you have to learn to love him.’”

“I told him, ‘I don’t love that man,’” Jackie says.

Despite her pleading for someone to listen, she returned. In the interim, she gave birth to a baby boy. Her third child. It was now 2012. Five years since she was introduced to her new husband. The cycle continued. Stay inside. Clean. Nurse. Cook. ‘Your husband is rich,’ her visiting aunts would say. ‘He can take care of you. Why don’t you just stay and raise the children?’

She just couldn’t. Later that year, when she was granted time out of the house, she left.

She didn’t care about the repercussions, the loss of financial security, or anything. She took her first-born, Shema, from her first marriage, and started a new life in Kayonza, a town she was familiar with from her previous waitressing gig. She knew Shema was the only child she could care for on a singular salary. Even if she wanted to, she couldn’t pass off Shema to anyone — not her first husband who was too far gone, or any relative. The other two children would have to stay with her second husband. At least they would have a wealthy father. They would be safe and have a better life with him. Certainly, she loved them, but she had no plans to put up a battle for custody.

Jackie searched for jobs, jobs and more jobs. One, the only, silver lining about being stuck inside her home in Kenya was that she had time to collect a teaching certificate online. In Kayonza, she bounced around teaching at boarding schools in the district wherever she was needed, but eventually quit. At least she was on her own. She could wander. She could make her own choices.

Finally, she found ZOLA, or fittingly, ZOLA found her.

Jackie working at her desk with ZOLA

ZOLA Electric is a company specialized in distributing renewable energy solutions to empower homes, businesses and families across Rwanda. Jackie started out under ZOLA working as a saleswoman receiving no salary, only commission. In 2015, she earned enough money to attend East African University in Nyagatare District as a business student paying for school on a month-to-month basis. Her bosses allowed her to leave early on Fridays and study during the weekend.

At college, Jackie was given the opportunities she deserved. She always knew she was intelligent. She was determined to show it. Her classmates nominated her as minister of agenda. She was class representative. She was a member of the debate club. She had her own office. She fought for the rights of students. She defended her dissertation on “The effect of renewable solar energy to the socio-economic development of Rwanda.” Life was turning around.

Jackie at graduation with her father

After gaining expertise from her newfound education, she was promoted within ZOLA. Starting in 2016, she was paid to be responsible for the 12 sectors within Kayonza District. Today, she holds the same position. She travels remotely going door-to-door selling the mission and products of ZOLA. She also spearheads conferences and meetings at the district offices.

She’s a self-made woman.

Jackie takes a deep breath, sits back and reflects on the telling of her story. The first time in a while she’s dissected the tremors of her past. She clears up timelines, gives reasons behind why she did what she did and spills drawn out exclamations when talking about the notions of “family” she’s endured.

Each time she brings up her ex-husbands, she begins to say their names, stutters and stops. She’s trying to forget them; erase them from her memory as if they were ill-advised pawn moves in a losing game of chess — except, all her life, her aunt, her grandpa, someone, had taken turns for her.

Finally, the next moves are hers.

Nearly three years ago, in Kayonza, Jackie began a new life. She didn’t have guardianship of all three of her children, but she did have Shema, her baby. Shema is her motivation. Shema is her everything. They’ve been through everything together. Last year, Jackie sent her everything to the Kayonza Youth Center to find an activity suitable for her free time.

“I wanted my daughter to do Kung-Fu,” Jackie says. “Shema went for one day and came home saying, ‘Mother, I want to go and play basketball. I will do that instead.’”

Shema (left), Jackie (right)

Jackie didn’t have a reason to say no. She had been told what to do, who to marry and where to run her entire life. Of course, she would guide Shema, but any daughter of her’s was going to make her own decisions. She permitted Shema to leave the solidity and structure of martial arts for the fluidity and sovereignty of basketball. After the fact, Jackie was comforted by the sight of her daughter with a basketball every day. She never had to guess if her little girl was wandering around town after school. She saw how much Shema loved the game and the friends she made dribbling around on the court.

When Jackie started going through bouts of depression, she looked for a distraction. She became so stressed her mind was flooded with destructive thoughts. The first person she turned to for answers was Shema. Jackie always insisted they solve their issues together and encourage each other. The two came up with the best solution they could conjure.

What made Shema happy? The only answer was basketball.

That’s how Jackie’s Shooting Touch journey began.

She called the library near the Youth Center for answers. She reached out to coaches and past Shooting Touch Fellow Jordan Dillard with an explanation of her situation. She watched videos on YouTube of James Harden and the Houston Rockets. She did her research. She didn’t care how, she just wanted to play. That’s when she found out she’d be a unique piece of the Shooting Touch culture in Kayonza. She’d be the only woman. She wasn’t surprised.

“I always go down to the Kayonza market and I talk to many women,” Jackie says. “They say, ‘I can’t have time for (basketball). I can’t leave my business.’ They want to. But some are selling for their survival.”

At the other rural Shooting Touch locations for women’s practice, the court is a sanctuary for maternal relaxation. It’s a place where a mother can pass off her newborn from her back, or suckled breast, when she wants a turn in the dribbling line. A place where no one can demand the crops to be tended or dinner to be served. A place where struggles are shared and best friends are made. For one hour in the day, basketball in the Eastern Province provides women a platform to break free from the damaging patriarchal principles of Rwandan society.

For Jackie, though, practice means something slightly different. Yeah, she’s the only grown woman but nobody cares. Her daughter no longer grabs for her breast but yearns for her companionship. The two of them build on that relationship as they sprint side-by-side. Basketball is Jackie’s energizer. She’s more tired when she rests at home than when she goes through layup lines and scrimmages. She went from not being able to reach the bike seat to leaping up for rebounds off a 10-foot rim. She breaks up teenage quarrels, joins in on laughter and breaks down huddles. She leads with few words, with her quiet strength.

While practicing, she also volunteers. She’s an advocate for the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF – FPR), the current political party in power in Rwanda. Her job, as secretary managing the FPR Student Committee in the country’s Eastern Province, is to monitor youth with drug use and oppositional/rebel ideas. Shooting Touch provides her the chance to interact with local students to understand their behavior. She receives no benefits from it. She takes pride inworking for her country.

One day, she wishes to serve her country in other ways. She wants people to know she has a vision. Her dream is to become a senator or a leader in parliament. She knows she must fight to get there.

“Women, wherever they lead, they can’t fail,” she says. “They understand, they love, more than men.”

Jackie running with other Shooting Touch Women to celebrate International Women’s Day

On a road usually meant for screeching busses, exhaust-spewing eighteen-wheelers and zipping motorbike chauffeurs, Jackie marched without a care in the world. She marched as a strong woman, one of nearly a thousand participating under the Shooting Touch umbrella. She marched because Saturday, March 16, 2019 was the annual Shooting Touch International Women’s Day Tournament, for which the Kayonza District declared a restricted car-free zone in celebration. The march would take place over a three-mile stretch. Final destination being the Nyamirama Court — the same one Jackie showed up to earlier that Monday.

Jackie arrived at the starting point an hour early. She greeted surrounding women with a soft smile and concerning questions. She swung her arm around the Kayonza Shooting Touch children, a mother and a teammate all in one. She acknowledged nearby men who were there to show support. I would say she was locked in politician mode, but the connotation of politician wouldn’t be fair to characterize Jackie — she cares way more than your typical policymaker.

At 10:00 am, the march commenced. In front, women held banners, beat drums, grasped hands and clapped during their favorite, rehearsed chants. Overhead, a storm cloud creeped slowly, almost mockingly, just waiting to ruin the celebration. When the rain fell within the first mile, and fell hard, no one stopped. Especially not Jackie. Her march turned into a jog. She smiled while she ran, hair and clothes soaking wet. She didn’t sing loudly, but her movements, like her words, like her spirit, didn’t waver.